Rizal Bagus Saktyono, Pelari Jawa Tengah yang Berpacu di Final Lari 100 Meter Putra

Pendahuluan Rizal Bagus Saktyono Dalam ajang perlombaan atletik tingkat nasional maupun internasional, kecepatan dan ketangguhan…

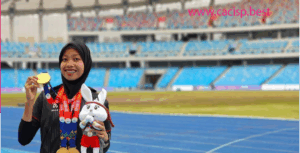

Saptoyogo Purnomo, Pelari Indonesia T37 Berprestasi di ASEAN Para Games

Pendahuluan Saptoyogo Purnomo ASEAN Para Games 2023 yang diselenggarakan di Phnom Penh, Kamboja, menjadi panggung…

Kipyegon Raih Emas Beruntun 1.500 Meter Putri untuk Ketiga Kalinya

Pendahuluan Kipyegon Raih Emas Beruntun Perjalanan atletik selalu dipenuhi dengan tantangan, semangat, dan pencapaian luar…

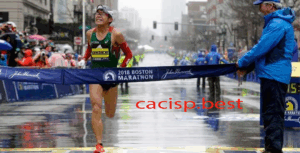

SOSOK Soh Rui Yong: Pelari Singapura yang Beri Contoh Kepedulian di SEA Games

Pendahuluan SOSOK Soh Rui Yong Dalam dunia olahraga, kompetisi seringkali diwarnai oleh rivalitas dan semangat…

Robi Syianturi: Atlet Lari Jarak Jauh Kebanggaan Indonesia yang Menorehkan Sejarah

Pendahuluan Robi Syianturi Indonesia dikenal dengan kekayaan alam dan budayanya, namun di dunia olahraga, negara…

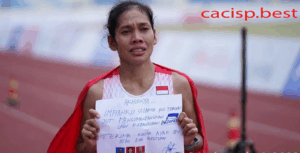

Triyaningsih Legenda Atlet Lari 10.000 Meter dari Indonesia yang Meraih 10 Medali Emas di SEA Games

Pendahuluan Triyaningsih Legenda Atlet Lari 10.000 Meter adalah salah satu atlet legendaris Indonesia yang dikenal…

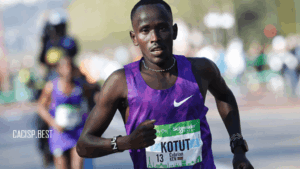

Agnes Tirop: Juara Lari 1500 Meter yang Meninggal Dunia Secara Tragis di Usia Muda

Pendahuluan Agnes Tirop, seorang atlet lari jarak menengah asal Kenya, dikenal sebagai salah satu pelari…

Nella Agustin, Pelari Putri Sumatera Utara, Raih Prestasi Gemilang di Nomor 200 Meter

Pendahuluan Nella Agustin menjadi perbincangan hangat di kalangan pecinta olahraga tanah air setelah penampilannya yang…

Dasmin: Atlet Lari Samarinda yang Berprestasi dan Inspiratif

Pendahuluan Dasmin Dalam dunia olahraga atletik, prestasi dan konsistensi adalah dua hal yang sangat dihargai.…

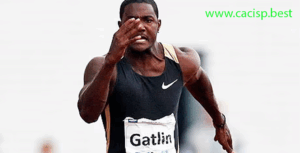

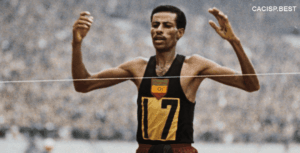

Purnomo Muhammad Yudhi: Sang Pengukir Prestasi Atletik Indonesia

Pendahuluan Purnomo Muhammad Yudhi Indonesia telah lama dikenal sebagai negara dengan kekayaan budaya dan keindahan…